Difference between revisions of "Main Page"

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

# [[Collecting Seaweeds on Macquarie Island with A.N.A.R.E., December 1960]] | # [[Collecting Seaweeds on Macquarie Island with A.N.A.R.E., December 1960]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | # [[Simple Arithmetic Proof that Captain Robert F. Scott’s Party did not Perish in 1912 due to Weather and Starvation]] | ||

| + | |||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

Revision as of 11:45, 12 January 2018

Contents

Simple Arithmetic Proof that Captain Robert F. Scott’s Party did not Perish in 1912 due to Weather and Starvation

Krzysztof Sienicki

Chair of Theoretical Physics of Naturally Intelligent Systems, Topolowa 19, 05-807 Podkowa Leśna, Poland, EU.

Captain Robert F. Scott’s Antarctic expeditions, like any human undertakings which have exploratory aspects - even recent ones - were bound to run into many different troubles and difficult times. Both of Captain Scott’s expeditions, but especially the Terra Nova Expedition [1] of 1910-1913 (British Antarctic Expedition 1910-1913), were life-threatening bold endeavors. They were highly complex logistical undertakings where humans, animals, machines, and nature played their roles.[2] In some respects, Captain Scott’s methods were archaic, but in other respects, they were innovative and ahead of their time.[3] Ever since the Terra Nova Expedition’s ship returned with the news from Antarctica in 1913, a great number of causes for the disaster have been offered, proposed and widely discussed. However, it was Captain Scott himself in his Message to the Public [4] who first presented a number of reasons for not being able to return to home base at the Ross Island (Hut Point/Cape Evans). The list of causes of the Captain Scott party’s disaster - both referred to by himself and later by various authors - is rather long. However, it is assumed that the final cause of the Captain Scott party’s deaths was slow starvation. [5] Here, we show a simple arithmetic proof that Captain Scott’s party, which consisted of himself, Dr Wilson and Lt Bowers, had full food/fuel rations until at least Mar. 27th, 1912. The result seriously and principally questions Captain Scott’s integrity in reporting actual causes of the party’s deaths back in late March 1912.

Captain Scott’s Terra Nova6 and Captain Amundsen’s Fram [7] expeditions were definite events, which during the planning and executing stages were reduced to numbers: miles per day, calories per day, temperature, efficiency, work, friction, etc. Both explorers and the members of their expeditions, in different degrees of proficiency and expertise, transformed these numbers into everyday life and actions. Although Captain Scott’s South Pole Journey was primarily a logistic undertaking, the fundamental aspects of it were neglected by historians, biographers, and hagiographers. Only a few specialized exceptions exist, scattered in professional journals. The majority of books concentrate on the nostalgic lamenting over the suffering of Captain Scott and his companions. Authors close their eyes to scientific analysis while arguing that Captain Scott’s expedition was a primarily scientific expedition.

Apparently, before going South in 1910, Captain Scott presented to the Royal Geographical Society a lecture in which he suggested that the ideal date to reach the Pole [8] would be Dec. 22nd. Since the account of the Nimrod Expedition (1907-1909) was already published, Captain Scott could figure that if he would follow Lt Shackleton’s route to the Pole, he would have to cross about 1345+97[math]\times2[/math]=1539 geographical miles in say [math]2\times52\times\left[30+22\right] days=104 days[/math][9], starting on Nov. 1st. It would mean that the velocity of the travelling party must be 16.3 miles per day, every day, for 104 days! A staggering figure. No contingency plan. No delays, no blizzards and no rest. How Captain Scott was expecting to reach the Pole on such an early date without dog sledging transportation will remain a mystery.

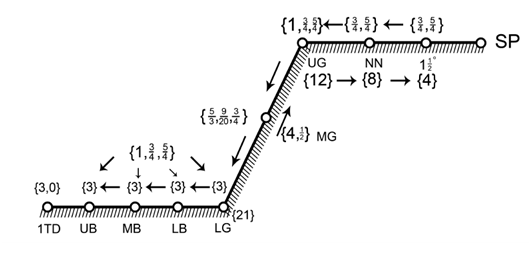

It appears that a detailed and final logistic plan concerning time, rations (food and fuel), distances, people and traveling means, was in place in early September 1911. One could only wonder what was so time-consuming for Captain Scott to figure out the Southern Journey rations and distances distribution along the route to the South Pole. Thus, a sledging journey, a 144-day window of opportunity, to reach and return from the South Pole was envisioned by Captain Scott. The key to this plan was the sustained sledging velocity, which was about 10.1 geographical miles per sledging day. In modern terms, the sustained sledging velocity can be understood as a long-term average of a stochastic process, in which the daily sledging distance was a bound stochastic variable. In terms of initial distribution of food and fuel rations, Captain Scott’s plan of the Southern Journey was straightforward and followed the 144-day sledging schedule. It can be divided into two stages: the Barrier stage, and the beyond the Barrier (the Beardmore and Plateau) stage. This division was not only a geographical one. It was, more importantly, the division resulting from Captain Scott’s overall mobility due to dog/pony/man sledging velocity, and the related potential possibility of food and fuel re-supplying party/depôts along the route at the Barrier stage. Once the parties started to ascend the Beardmore, they were beyond recall and on their own. From the foot of the Beardmore Glacier, the initial rations of food and fuel were only diminishing. The distribution of food/fuel rations is presented in Fig. 1.

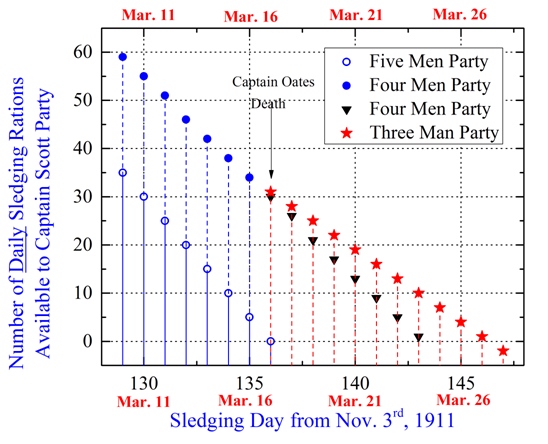

It is evident that the returning Captain Scott party of five men (himself, Dr Wilson, Captain Oates, Lt Bowers and P. O. Evans) started each returning leg between depôts with the allocated maximum of food/fuel rations to support the party until the next depôt was reached. Thus, upon reaching Lower Glacier Depôt on Feb. 18th, 1912, the party collected 1¼ sledging unit, altogether 35 daily rations for 5 men. However, a day before this, P. O. Evans died. Consequently, the food/fuel rations allotted to him were not consumed. The four man party continued sledging. On Mar. 17th, 1912 Captain Oates committed suicide. As a result, food/fuel rations originally allotted to him were not consumed. Now, it is evident how one could calculate actual food/fuel rations available to the Captain Scott party. The outcome of these simple arithmetical calculations is depicted in Fig. 2. It is the main result of this paper.

Although the conclusions from an examination of Fig. 2 are rather palpable, the following comments seem to be pertinent. This figure is indeed an illustrative one. If the party was sledging as a five man party as originally assumed, it would be out of food/fuel on Mar. 16th. However, due to the death of P.O. Evans on Feb. 17th the party was a four man party, and thus every sledging day one ration originally meant to be consumed by P.O. Evans was “saved” and later consumed by those who were alive. The full food/fuel rations for a party of four would end on Mar. 25th. In reality, Captain Oates perished on Mar. 17th and one more time, extra rations were “saved”. The party of three, Captain Scott, Dr Wilson, and Lt Bowers could sledge on full rations until Mar. 27th, 1912. This simple arithmetical result contradicts what is known from Captain Scott’s account in his diary. It questions Captain Scott’s entry on Mar. 19th that "\ldotsWe have two days' food but barely a day's fuel." In reality on this day (see Fig. 2), the party of three (Scott, Wilson, and Bowers) had eight (8) days of full food/fuel rations. It completely undermines Captain Scott's account on Mar. 22th and 23rd that "\ldots no fuel and only one or two of food left \ldots". As the deaths of P. O. Evans and later Captain Oates were unexpected sources of food/fuel for these alive, the role of ponies, according to Captain Scott's as an additional food supply for returning parties remains a mystery. From the onset Captain Scott, by not taking pony food for their return leg, was tacitly assuming that the ponies would be shot somewhere before the entrance to the Beardmore Glacier. Since eating pony meat was not a taboo, as, in the case of dog meat, one obviously must consider the addition of pony cutlets into the returning parties' menu.

Upon arriving at Shambles Camp/Lower Glacier Depôt, something extraordinary happened. The Captain Scott party, in addition to the full food/fuel10 rations depôted along the return route, found an abundance of food - pony cutlets stored in December 1911. The presence of pony cutlets at Shambles Camp was obviously not surprising. What is startling is that Captain Scott and his party, casually and bordering on negligence, did not take all of the pony cutlets. Although Captain Scott on Feb. 18th clearly acknowledged "plenty of horsemeat" at Shambles Camp, in the following days he took relatively little advantage of pony cutlets. We do not know the exact numbers or how many pounds of cutlets were obtained from the ponies. However, using a conservative estimation11, one can figure that these cutlets alone would have been sufficient to feed the Captain Scott party until One Ton Depôt was reached. The weight of a pony varies from 400-800 lb, and if about \frac{1}{10} of this pony mass was transferred into pony cutlets, it would give 4080 lb from one pony. Since five ponies were shot at Shambles Camp, this yields 200-400 lb of cutlets. If one person was daily consuming 2 lb of these cutlets, then the pony meat depôted at Shambles Camp would have been sufficient for (200–400)/2 = 100–200 days for one man. And because Captain Scott sledged from this camp in a 4-man team, it would translate into 25-50 sledging days. Taking a middle value of this estimation, one must conclude that the pony cutlets from Shambles Camp could have fully supported Captain Scott’s party food intake for well over a month of sledging. Yet Captain Scott only refers to eating pony meat from Feb. 18th through Feb. 28th. Since the distance from Shambles Camp to Hut Point is about 349 miles, the pony cutlets would have been sufficient to feed the party all the way back. In a similar fashion, the distance between Shambles Camp and One Ton Depôt is 231 miles; Captain Scott’s party could have easily reached it sledging exclusively on rations of pony cutlets. Provided that the first pony (Jehu) was shot on Nov. 24th, 1911 and that this location was reached by the returning Captain Scott party on Mar. 3rd/4th, 1912, the possibility of reaching One Ton Depôt and feeding on pony cutlets becomes a certainty. Let me stress here that the above is valid without the party’s use of food originally depôted on the Barrier. None of the above happened, and Captain Scott’s party made very little of the pony cutlets. In summary, it was shown that due to deaths of P. O. Evans and Captain Oates, the remaining party of four and later three (Scott, Wilson, and Bowers) had full food/fuel rations to Mar. 27th, 1912.12 This finding and almost entire neglect of pony cutlets during the return leg extend a list of deceits reported by Captain Scott in late February and March 1912. A more extensive examination of the above and many additional issues is presented in the author book titled Captain Scott: Icy Deceits and Untold Realities.[2]

References

[1] Robert F. Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition: Being the Journals of Captain R. F. Scott, R. N., C. V. O., Vol. I, Dodd, Mead & Company, The University Press, Cambridge, USA.

[2] Krzysztof Sienicki, Captain Scott: Icy Deceits and Untold Realities, Open Academic Press, Berlin-Warsaw, 2016.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Robert F. Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition: Being the Journals of Captain R. F. Scott, R. N., C. V. O., Vol. I, Dodd, Mead & Company, The University Press, Cambridge, USA, cf. p. 414.

[5] Colin Martin, Scientists to the End, Nature 481(2012)264; Roald Amundsen, My Life as an Explorer, Doubleday, Page and Company, Garden City, 1927, cf. p. 71.

[6] Robert F. Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition: Being the Journals of Captain R. F. Scott, R. N., C. V. O., Vol. I, Dodd, Mead & Company, The University Press, Cambridge, USA.

[7] Roald Amundsen, The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram” 1910–1912, John Murray, London, 1912.

[8] Robert F. Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition: Being the Journals of Captain R.F. Scott, R.N., C.V.O., Vol. I, Dodd, Mead & Company, The University Press, Cambridge, USA, 1913, cf. p. 376; Robert F. Scott, Plans of the British Antarctic Expedition, 1910, The Geographical Journal 36(1910)11–20, cf. p. 16.

[9] Nov. 1st through Dec. 22nd .

[10] Provided some \frac{1}{10} less fuel due to tin leakage. For calculations see Krzysztof Sienicki, Captain Scott: Icy Deceits and Untold Realities, Open Academic Press, Berlin-Warsaw, 2016, cf. section 9.3, p. 345-365.

[11] Krzysztof Sienicki, Captain Scott: Icy Deceits and Untold Realities, Open Academic Press, Berlin-Warsaw, 2016, cf. section 9.4, p. 365-376.

[12] Krzysztof Sienicki, A Note on Several Meteorological Topics Related to Polar Regions, The Issues of Polar Meteorology 21(2011)39–76.

Zeitgeist happenstance, or coincidence of Captain Scott’s élan vital: Part I - Prolegomenon

Krzysztof Sienicki

Chair of Theoretical Physics of Naturally Intelligent Systems, Topolowa 19, 05-807 Podkowa Leśna, Poland, EU.

ABSTRACT

Captain Scott’s journey to the South Pole in 1910–1913 was an extraordinary exploratory and social event, galvanizing many people, then and now. The question of his journey’s origin and aftermath from a social perspective is addressed. This approach sheds new light on this journey’s logistics and quasi-religious canonization of Captain Scott.

if it was so, it might be;

and if it were so, it would be;

but as it isn’t, it ain’t.

That’s logic.

Lewis Carroll, “Through the Looking-Glass”

Of late, there has been much interest in Captain Robert F. Scott’s journey to the South Pole. In these accounts, though in a zigzagged way, the matter was gradually disguised to portray Captain Scott as a hero and especially a scientist, like what was committed by (Martin, 2012). Attribution of these virtues was not happenstance, but rather a simple marketing notion: stories out of thin air that the common people become heroes and would-be scientists simply sell. An armchair explorer readily falls into the trap of following Judeo-Christian values (goals) via suffering and hard work. Suffering and especially recognized suffering means a battle –in our case, a battle for Captain Scott’s soul. However, Captain Scott’s suffering exemplifies all virtues of Britishness – a battle for Britain as an Empire, and the armchair explorer, as an individual and a member. In short, a zeitgeist notion emerges and self-propagates among individuals, who are ready to commit all delinquencies to defend deity and prepare themselves for even more fine-tuned glory.

The above moral setting, convoluted with the physical remoteness of action, its literary and narrative appearance through the only source, Captain Scott’s journal (Scott, 1913), matches the structure and power of the imaginative medieval world-view poem, the Divine Comedy (Divina Commedia) by Dante Alighieri in the early 14th century. Over time, the Divine Comedy became a descriptive foundation of Christian mysticism, and Captain Scott’s journal turns out, for some, to be a vivid narrative of a new uncanny Tennysonian final utterance – to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield – a quasi-religious counterfactual canonization of the South Pole journey’s par-ticipants.

Inferno (Hell). Antarctica, then and now is a Hell, an environmental Hell. It is not habitable and only a narrow spatiotemporal window exists for human endeavors in Antarctica outside the doors of research stations. However, even this middle summer window does not permit a lei-surely existence and exploration. Our existential experiences and Anglo-Saxon utilitarian think-ing cannot be transferred/applied to the hellish Antarctic environs. The blizzard may come in minutes, without apparent warning and cause. Antarctica is a Hell in the Divine Comedy, a physical space dotted by blizzards, crevasses, and mirages. Then and now, even the most adven-turous explorer cannot formulate hypotheses non fingo of safe passage and life in Antarctica.

All the way from Cape Evans, the Captain Scott party’s hypsometer was indicating a systematic relative height increase as they progressed toward the Pole. And then, right on the Antarctic Plateau and right on Jan. 13th, 1912, some 51 geographical miles from the Pole, Captain Scott conspicuously noted in his diary "It looks as though we were descending slightly…" What awaited his party at the Pole; a hollow Earth with a grand opening to the underworld? After all, ostensibly educated notions were advanced, and the literary narratives of Verne, Poe, and a number of others existed. Even my former neighbor Ferdinand Ossendowski (Ossendowski, 1922) believed so, many years after.

Captain Scott, however, pressed on, and there was no Hollow Earth, but the Hollow Souls of the party after being stabbed with the spire of Captain Amundsen’s black flag. It was Captain Scott’s Inferno and Captain Amundsen’s triumph at a grand featureless theater scene set at the Pole. There were hardly any spectators, but what a drama. With the black flag intro, a tent as the main part, and the final request to deliver a letter. The Empire reduced to the post office; a spas-modic laugh of history. Captain Amundsen and others, ..., emerged from the northern mists and humiliated the Empire. Enter a person from what was then formerly a mere member of the United Kingdom's of Sweden and Norway, and then "All the daydreams must go". Right at Cap-tain Scott's Pole, the South Pole, Captain Scott met his nemesis: false hype, British hypocrisy, and the blinded inability to perceive Antarctica as it was, not as a British playground. It was na-ture’s task field.

Purgatorio (Purgatory).Though they were alive, the Antarctic Plateau leg of the return jour-ney was their Purgatory an immense surface of snow through which all of them must pass. We do not know how, but it is certain, that thoughts crept into their individual and group feelings. Each time their ski poles pierced the Plateau’s surface on the way back, and with every period of time elapsed, their event horizon, the boundary, was shrinking to Antarctica itself. More pre-cisely, to the record cones of points of no return; individually and collectively. One and all were gazing at Captain Scott, who was probing Uncle Bill, his confessor and éminence grise of the expedition.

At first, they met the Pole with a denial. On Jan. 16th, 1912 a day’s march from the Pole "Bowers' sharp eyes detected … a carin" or "sastrugi". But "soon we knew that this could not be a natural snow feature". Indeed, it was a sinister black flag planted by Captain Amundsen. The beacon of the slaying of a beautiful British superiority hypothesis by the ugly fact of Captain Amundsen's dominance on all grounds.

It was not long before they recognized that the denial could not be continued. The anger poured in. The pariahCaptain Amundsen trespassed on Captain Scott's territory and breached a gibberish polar etiquette on at least five counts. Forget science, forget exploration and discovery, it was an anunacceptable act that "one explorer is walking on another explorer’s continent". If, when told by Lt. Campbell on Feb. 22nd, 1911, that Captain Amundsen had established his base, Captain Scott's party was "furiously angry, and were possessed with an insane sense that we must go straight to the Bay of Whales and have it out", then what a fury mixed with despair was released at the South Pole. However, though not at a definitive time, it became obvious to Captain Scott that like Odysseus, he was trapped between the Scylla and Charybdis of returning in personal shame, public shame, and under professional assault worse than that he had suffered from the Discovery Expedition; or not returning alive from Antarctica to escape the former. Mile after mile, day after day; while sledding back over the Antarctic Plateau, Captain Scott mulled over Odysseus’ dilemma. They kept a fine sustained sledding velocity to meet returning depôts at predefined time intervals, which had been additionally stretched by taking Lt. Bowers to the Pole. It slowly crept into Captain Scott's head that "I have always taken my place, haven't I?" Indeed it was a process, slowly increasing its load, slowly to the degree of not noticing each infinitesimal terrace. Dante envisioned seven terraces of Purgatory, but for Captain Scott, it was an Antarctic Pla-teau Purgatory; white and endless sin by its very existence. If there had not been a Pole, Captain Scott would not have committed his soul to it. A few days before sledging to the South Pole, Scott professed that "If he [Amundsen] fails, he ought to hide!" (Pound, 1966).

What would Captain Scott’s destiny be if he failed not only to reach the Pole but to be the first to do it? To get financing and all the needed support, the national and imperialistic notions were exposed, stressed, and underlined quite publicly by Captain Scott from 1909–1910 in vari-ous public speeches recorded in newspapers. If not us, tacitly argued Captain Scott, then who? Was not the Pole a part of “the empire on which the sun never sets”? From Captain Scott’s pers-pective, should not he “ought to hide” if he failed to be first at the South Pole? Or – on the con-trary to Captain Amundsen – was he immune to social pressures?

His wife Kathleen’s instructions to him were explicated (Herbert, 2012) "[it] wouldn’t be your physical life [sic] that would profit me and Doodles [their son Peter] most. If there’s any-thing you think worth doing at the cost of your life – Do it". And it was not a literary allegory, as Kathleen Scott was not Matilda of Tuscany.

Kathleen's "Do it" was meaningless without Captain Scott's Purgatory tale, a well-defined principal entity possessing traits of omniscience, omnipotence, omnipresence and divine simplicity. However, Kathleen's "Do it" should "profit me and Doodles" and not a real or imaginary deity. The Empire was second to none on the list. Death for the Empire's benefit was a crucible to their eternal salvation and a tacit condition of Kathleen's request.

From Feb. 2nd, 1912, the South Pole party was dogged –as described in Captain Scott's diary – by a long chain of events of unpredictable natural origins, which despite the party's fight and will finished them off.(Sienicki, 2016) "For God's sake look after our people" Captain Scott exclaimed in his last diary entry and committed in his Message to the Public one of the most dubious press releases in history The causes of the disaster are not due to faulty organisation, but to misfortune in all risks which had to be undertaken … Every detail of our food supplies, clothing and depôts made on the interior ice-sheet and over that long stretch of 700 miles to the Pole and back, worked out to perfection … But all the facts above enumerated were as nothing to the surprise which awaited us on the Barrier. I maintain that our arrangements for returning were quite adequate, and that no one in the world would have expected the temperatures and surfaces which we encountered at this time of the year.

And a few lines down, Captain Scott made his appeal to the Empire by explaining his sacrifice of the souls in Purgatory I do not regret this journey, which has shown that Englishmen can endure hardships, help one another, and meet death with as great a fortitude as ever in the past. We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us … Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman.

At first, it seemed a complete account. From then on, their souls awaited "the verdict of their hearings". Not for long. Already when the last tent was found on Nov. 12th, 1912, the heroism of Captain Scott and his comrades was emphasized, with its apogee back in London on Feb. 14th, 1913 with the zeitgeist's-whispering vortices in the galleries of St. Paul’s Cathedral – Oh! England! Oh! England! What men have done for thee. (Crane, 2006)

Captain Scott’s story "stirred the heart of every Englishman" and transcended to the state of self-sacrificing purification for the love of the Empire, which in deity-like gestures of eternal zeitgeist and, through trial of its selected members,removed all the remnants of imperfection from Captain Scott and his comrades, who "…have been willing to give [our] lives to this enterprise, which is for the honour of our country". The gates of the garden of Eden were open, and Captain Scott sledged in with his comrades. Or, like Odysseus/Ulysses, were they banished to the eighth circle of the Inferno?

It is fair to assume that on the very day of Feb. 14th, 1913, in St. Paul’s Cathedral, a social inquisition combating the heresy of the human origins of Captain Scott’s life and exploits was materialized. From then on until today, as in many small or big inquisitions, actions of otherwise deplorable moral (ethical) values were allowed at all cognition levels.

In this series of papers, I will look critically at major events of Captain Scott’s journey to the South Pole.

REFERENCES

Crane, David, Scott of the Antarctic, A Life of Courage and Tragedy, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2006.

Herbert, Kari, Heart of the Hero: The Remarkable Women Who Inspired the Great Polar Ex-plorers, Saraband, 2012.

Martin, Colin. "Antarctica: Scientists to the end." Nature 481.7381 (2012): 264-264.

Ossendowski, Ferdynand Antoni. Beasts, men and gods. EP Dutton, 1922.

Pound, Reginald. Scott of the Antarctic, Cassell, London, 1966.

Scott, Robert F. Scott’s Last Expedition: Being the Journals of Captain R.F. Scott, R.N., C.V.O., Vol. I, Dodd, Mead & Company, The University Press, Cam¬bridge, USA, 1913.

Sienicki, Krzysztof, Captain Scott: Icy Deceits and Untold Realities, Open Academic Press, Berlin-Warsaw, 2016.